Extra: Erik Matson on Adam Smith, David Hume, and the New Paternalists

In Erik Matson’s interview on The Great Antidote Podcast with Juliette Sellgren, Matson talks about his book New Paternalism Meets Older Wisdom: Looking to Smith and Hume on Rationality, Welfare, and Behavioral Economics, and the problems with paternalism generally.

Matson differentiates between “classical paternalism” and “new paternalism”, which he sums up as “old paternalism, I know what's good for you. I'm going to force you to do it. New paternalism, what's good for you? I'm going to help you do it.” [14:25]

The most well-known example of new paternalism, Matson points out [14:54], is “libertarian paternalism”, the theory that policymakers can use “choice architecture” to lower the cost of making the choices people want to make.

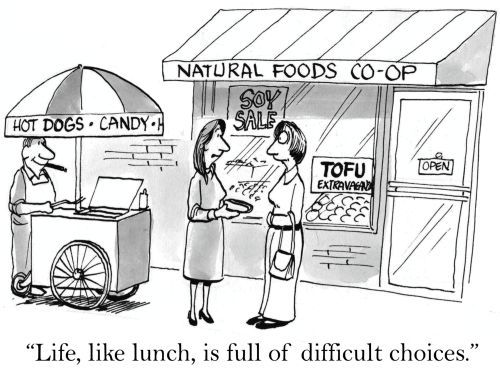

”Choice architecture” refers to designing how the options available to us (including the option to do nothing) are presented. There are a few common examples. One is that a school hoping to influence what students take from the cafeteria might put fruits, vegetables, and nutritionally dense foods near the beginning of a lunch line to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption. Another is that people might be automatically enrolled in organ donation programs from which they can withdraw or the presumption can be that their organs may not be donated unless someone opts in. Libertarian paternalism would suggest the adoption of prominently displayed fruits and vegetables and the “opt-out” model for organ donors on the assumption that almost all people want to donate their organs.

This presents an opportunity to talk about the limits of knowledge and our ability to help one another, especially in an explicit, knowable sense.

Price, purchases, preferences

Sellgren and Matson discuss the difficulties involved in discovering someone’s preferences. While new paternalism claims to aim for achieving some ideal that individuals would choose absent constraints, an idea of “true” preferences. That's not the only way to use the word.

Sellgren talks implicitly about revealed preferences as one route to understanding our true preferences:

it's hard to know what an individual's preference is to have this knowledge…which is why we have this idea of revealed preferences. Even I don't know what type of candy bar I prefer because I'm not counting every single time I buy a candy bar or consume one—or maybe I say I don't prefer it, but in reality, I do because I always choose it. [38:15]

As Sellgren’s musing suggests, this is tricky. Thinking of purchasing decisions as a way of revealing deeper, “true” preferences can be misleading. A purchase decision combines more than just our preferences—it’s (1) the options available to us, (2) the price of each option, (3) our budget constraints, and, yes (4) our preferences, which are complicated by their rankings and strengths.

In Sellgren’s episode with Ryan Bourne discussing his book The War on Prices, She and Bourne discuss prices, illustrating their discussion with the baby formula shortage in 2022 (Sellgren and Bourne, 4:34).

Support for and understanding of prices has degraded along several fronts. Bourne’s concern in the discussion is limited to one type of price control: price ceilings (that is, legislating a maximum market price). He is concerned specifically with the call for price ceilings in the face of supply disruptions or inflation.

The stakes of the baby formula shortage make the distinction between purchasing decisions and preferences stark. Parents who needed formula during the shortage were not free to fulfill their ideal preferences but stuck, always, with their best guess at an “optimal” solution. The best decision available was unlikely to reveal much about parents’ preferences beyond desperation to make sure their baby was fed.

Sellgren and Matson also discuss [19:13] a conception of preference discovery in which work is needed to discover preferences. In this formulation, new paternalist interventions to lower the costs of certain decisions might frustrate individual preferences. Here is where thinking in terms of purchases can help, not confuse, the discussion. It seems unlikely that costs never matter to whether individuals can fulfill their preferences.

Someone who says they want to quit smoking is not simply forgetting their “true” preferences when they fold to addiction and buy cigarettes when standing at a cash register for another purchase. Someone who says they want to feed their children more fresh fruits and vegetables but can’t afford to fill their shopping cart in the produce aisle is not mistaken about what they really want. In both cases, purchasing decisions can’t tell us about overall preferences unless the cost of the expressed preference becomes bearable.

Realistic policymaking

If all we are interested in is helping people by their own lights, then the problem of high costs standing in the way of fulfilling preferences should matter. It’s not all that’s on the table—contrast Matson’s favourable mention of civil society to apply pressure on individuals to make different choices [36:40] with individuals imposing their own “nudges” as in the case of an alarm clock [37:35]. But it still matters.

There are two insurmountable problems with “new paternalist” government policy. First, the knowledge problem—some preferences really are tacit or unexamined. Second, government-level policymaking should take the form of general rules, not targeted interventions in individual lives, even if the knowledge problem could be overcome.

Government policy cannot be individualized enough to meet the standard of new paternalism. As Matson puts it, “the new paternalism claims it's helping people do the things that they want. Otherwise, we simply have regulation informed by behavioral research. Which is fine, but then you have to justify the regulations.”

The complexity of individual preferences, the difficulty of understanding tacit knowledge even through prices, and the lessons from David Hume and Adam Smith combine to show us that at the end of the day, “nudging” regulators can’t speak for us. They are stuck justifying their policies some other way. The new paternalist standard can’t be met.

Can we nudge you toward more content?

Alejandra Salinas’s Adam Smith as Behavioral Economist?

Hairuo Tan on Matson's New Paternalism Meets Older Wisdom (Book Review)

Leonidas Zelmanovitz’s Behavioral Versus Free Market Economics at EconLib

Behavioral Economics, by Sendhil Mullainathan and Richard H. Thaler. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

Richard Thaler on Libertarian Paternalism at EconTalk

Alejandra Salinas’s Adam Smith as Behavioral Economist?

Hairuo Tan on Matson's New Paternalism Meets Older Wisdom (Book Review)

Leonidas Zelmanovitz’s Behavioral Versus Free Market Economics at EconLib

Behavioral Economics, by Sendhil Mullainathan and Richard H. Thaler. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

Richard Thaler on Libertarian Paternalism at EconTalk