Tawni Hunt Ferrarini on Teaching Hayek

How do you teach about a man who does not fit neatly into a box? Hayek is one such man, and today, we tackle the difficult task of putting him in a box. We conclude that we cannot put someone like F. A. Hayek into boxes such as “economist” or “philosopher” or “political theorist”, because he did it all. How and when do you teach the ideas of a man who did it all?

I’m excited to welcome Tawni Hunt Ferrarini to the podcast today to talk to us about teaching Hayek and his most important ideas. Ferrarini is a co-author of Common Sense Economics and an economic educator worldwide. We go through multiple ideas of in-class examples and places his thought could be applied in the context of modern education. Keep listening to hear me talk about how I, Pencil is scary.

Want to explore more?

Want to explore more?

- Explore the Common Sense Economics website.

- Tawni Hunt Ferrarini, Real Life Economics: Rational or Complex, at EconTalk.

- Art Carden, Read Hayek as if Your Children's Lives Depend On It, at the American Institute of Economic Research.

- Ryan Yonk on the China Dilemma, a Great Antidote podcast.

- Come explore Hayek with us in these two upcoming Online Programs led by Dr. Ferrarini:

- A Timeless [asynchronous] discussion, October 28-November 3 in the LF Portal.

- Dive Deep into Hayek's "Use of Knowledge in Society," a one session Virtual Reading Group, November 13th.

Read the transcript.

Juliette Sellgren

Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition. Hi, I'm Juliet Sellgren, and this is my podcast, the Great Antidote named for Adam Smith, brought to you by Liberty Fund. To learn more, visit www.AdamSmithWorks.org. Welcome back. Today on September 17th, 2024, we're going to be continuing with the mini-series that is celebrating the 50th anniversary of Hayek's Nobel Prize. I'm really excited today to welcome Tawny Hunt Ferrarini to the podcast to talk to us about teaching Hayek and teaching economics. She is a co-author of Common Sense Economics, which makes her a common sense economist, and she's an economic educator worldwide. I'm so excited to have this conversation today. Welcome to the podcast.

Tawni Ferrarini

Oh, thank you, Juliette, for the invitation. And thank you listeners for listening. I appreciate the time you're going to share with me, and my hope is that I can help you learn more about Hayek and the relevancy of his ideas in this modern world.

Juliette Sellgren

So before we get started, this question might be relevant, but doesn't have to be- what is the most important thing that people my age or in my generation should know that we don't?

Tawni Ferrarini (1.27)

Spend more time with your elders? Because you don't want to reinvent wheels and you're doing exactly that, talking with the various scholars and such, but also spend time with their parents, your grandparents, people that you don't know. And a lot of the lessons that you'll learn throughout life they've already learned. And you'll see even in our discussion today, you don't have to reinvent these wheels and yet your generation has a tendency to want to do that. And that's okay. Remaking is all right. But yeah, spend time with your elders.

Juliette Sellgren

I love that response maybe because it makes me feel good about having a podcast among other things, and the fact that grandparents tend to like me.

Tawni Ferrarini

I'm wonderful too. I've always spent time with my elders and people known and unknown, so it's wonderful.

Juliette Sellgren (2.22)

So I have a question that kind of goes against the grain of your response maybe. I think, and it will lead us into this conversation, I hope. I think a lot of the classical liberal tradition, a lot of more maybe Austrian, less empirically modern, if that's communicative of that idea. Economists and people who follow actually the history of thought. We as a group tend to lean into this, not remaking the wheel, but I think we have a lot of a hard time that doesn't quite make sense, but we have a hard time remaining relevant. And it's funny, I was having this conversation with Don the other day and remembering and kind of marinating in these ideas that Hayek has and these things that he's talking about and realizing that they're even more relevant today than they maybe even were at his time, and that they can help us even more. How can we maybe not remake the wheel, but kind of republish the wheel in a way that is snazzier and more TikTok friendly? Maybe. Is there a clear way to do that? Because I think I, especially trying to teach this stuff struggle with not sounding like I'm just regurgitating something that someone else said and making it super modern, relevant to the current day and actually competitive with ideas that seem like a newer wheel, even if they're not.

Tawni Ferrarini (4.03)

Right. I mean, this is a great question, and I think that you're bringing up some points, several points that I think explains why Hayek is not as popular as he should be and why in his battle with [John Maynard] Keynes and the ideas that they both supported. Hayek appeared not to come out on the popular end. Because if you look at his personality and you consider his background that Hayek, he's a towering figure in economic theory throughout the 20th century when you kind of encapsulate him and you bring him into the free market economic space, you're going against the grain, especially during turbulent times. And the other Hayek scholars and people on your podcast will delve into the intricacies of Hayek’s work and scholarship. My hope is that by us having this conversation, we're going to lift up Hayek, we're going to bring him into the modern century, and we're going to make those Austrian School of theories in the applications so that we can make this thought leader who championed free markets in minimal government intervention, relatable, understandable, and people can really get their arms around why, by executing or practicing his ideas, we can actually help ourselves live better and more comfortably than if we chose an alternative.

And that's what we haven't done a very good job of doing. And I think Austrian economists have a really hard time in the TikTok space because they have heavy jargon. They're laden with theories. And in order to explain their theories and the practicality of them, they go into these long dissertations and people just start tuning them out. They just say, no, huh, I'm shrugging my shoulders, I'm walking away. And so in today's social media riddled world, it's more important that people like you and I get these ideas out. We do it in sound bites. We do it in a way that if people find interest that they can quickly go to the primary sources or find more information about how or what these ideas are and how people act on these ideas. Again, they can live better and help others do the same.

Juliette Sellgren (6.48)

The thing that I think is kind of complicated with the Hayek story though, what comes to mind very vividly is the rap battle on YouTube, which is, it's fantastic. This is honestly a piece of media. Now this is going to be like a meta multilayered commentary. It's a piece of media that really communicates the ideas in an understandable and catchy way, kind of like Hamilton. And it also has a strong visual attached. So not only is it a great example, but I really think of how you see Keynes's kind of exemplified and represented as being this super popular, very cool swaggy guy. And on the one hand, he has catchier sound bites. It's the animal spirits in the long run we're all dead. But then on the other hand, these guys use more math. They write books that are harder to read. And so I don't really know how to reconcile those two things. And what ends up with someone like Keynes's being on top, is it that he tells people kind of what they want to hear and that what Hayek has to say is more, I don't know that it requires more brain work, even if he says it in a way that is less mathematical and more example heavy. I'm not quite sure what to make of all of that.

Tawni Ferrarini (8.17)

Well, and this, I think when I talk to young people, especially young people who are considering economics as a major, as undergraduates or pursuing PhDs in the subject, you ask them what draws you to the profession? And the type of person that's drawn into the profession often is the type of person, with the exception of the Austrians, where they in this day and age, the popular, the mainstream is built around these mathematical models and sophisticated analysis, and it's riddled with data econometrics, and the list goes on when you're relating to the person in the general population into the masses, that's not their space. It doesn't mean that there isn't a rule for that person. It's just not their space. And they have a right to have their space just like we have a right to have hours. I think it takes more people like you and me to communicate across the spaces and say, Hey, there's something interesting over here.

Come on over. And we don't do that by bombarding them with models and data. What we do is we speak their language. And I think that that getting back to Keynes, that's what he did. Well, he ran in some very interesting circles. He was married to a dancer. He was by some accounts, very flamboyant in his personality and such. And people were drawn to him. They wanted to follow him. By contrast, you hop on over and you consider look at the pictures of Hayek and you consider his lifestyle. I mean, he was very much a professor. I mean, he was a towering figure. He is an Austrian economist. He spent most of his time at the London School of Economics in his later years he was at the University of Chicago, and then he spent time in Freiburg. And these are all places that have a lot of prestige and they have a lot of serious academics around. And it's a different environment than Keynes's found himself in very much. I mean the ones that made a difference and had an impact on people, especially in political circles. And we'll get into that conversation in just a moment.

Juliette Sellgren (10.40)

So what I'm kind of hearing is that as much as I wish we could just make professors cool, I mean I think professors are cool, but I don't think the TikTok crowd is as convinced of this fact as I am, especially as maybe a professor hopeful, who knows. But I guess what we need is a popularizer need a Keynes type messenger to deliver the message of Hayek. We need to put some sunglasses on The Road to Serfdom.

Tawni Ferrarini

Yes.

Juliette Sellgren (11.16)

So how do we do that? Because as much as I said that earlier that Hayek's work is verbal and not mathematical, and so it's easier to understand, especially Hayek of all of these guys, this intellectual line of thought that we kind of fall into. As much as it's understandable verbally, the stuff that Hayek talks about is the complexity of the economy and information systems. And I've been really struggling to communicate this, not only because in school, just by the model of the way that college classes work, we don't have a ton of time to focus on what's in a price. We talk about the demand curve and we need to communicate the relationship between price and quantity and other factors and quantity and price. And price is a signal, but we don't have time to really delve into that idea. And even if I did, I've read the use of knowledge in society five times, and I'm only starting to get it. So how do we communicate this? Because he has made it as easy as I think it can be by putting it into words like this. But how do you in a limited time communicate this to a student who's not going to be able to read it that many times and spend all their time thinking about it?

Tawni Ferrarini (12.41)

Well, their opportunity cost is too high. They're not going to read Hayek as many times as you have, and they're not going to be deliberate in their reading and try to really understand what's going on. But what they will do is they will spend time. Your students will spend time with you because their grade matters. So rather than giving them what I call these like ah-hah moments or the opportunities to shrug their shoulders thinking, alright, all I have to do is memorize this, get through the exam and put this topic to bed, supply, demand, equilibrium markets balancing out. What you want to do is you want to get away from the economic speak and move into the heads, into the minds and into the hearts of your students. So I like telling these little stories. And for example, most of the students, I'll survey them, what interests you?

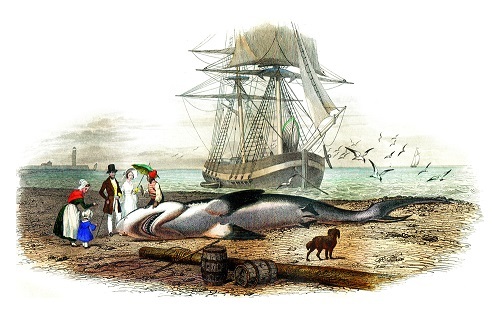

And we have so many political, social, and economic issues swirling in the world today. It really is a potpourri of topics. But usually I find that there's a good chunk of students who are interested in saving different animals from extinction. And what I do in order to explain the beauty of markets and the power of market signals and prices is what I'll do is I'll ask them to just imagine themselves traveling back into time and to go into the mid 18th century and say there were so many populations that were struggling and people were stressed, especially the most marginalized groups. And then I'll say they lived in a time when having electricity wasn't an option. Heck, kerosene oil wasn't even around what their main source of fuel was at that time, whale oil. And we will bring 'em back to that very real time for those people.

And as some say it sounds, but they get kind of interested because they know that there's something there that they're interested in. They want to save the whales, even if it's in the 18th century. And it was like, oh, well, let's introduce a little of the Hayekian wisdom and explain how Hayek can help save the day, even the whales. And so then I'll help draw a picture for them and say, okay, the cities during this period were starting to get lit literally with whale oil lamps. And what did this mean? It meant like many hot commodities. There was a surge in demand which pushed up prices. People wanted to work longer hours, they wanted to enjoy having light in the evenings at their homes, and the list goes on. But what consequently happened next was the whales were nearly harvested into extinction. They started to vanish faster than free pizza on move-in day across college campuses.

And so when we fast forward and we think about what happened there, we see that, oh, there was a prompt that higher oil prices, excuse me, really kind of pushed some people into desperate times or into modes because not everyone could afford the whale oil. When the entrepreneurs, they understood the people who were doing the whaling that as whale prices climbed and the marginal benefits derived from each additional whale that was harvested would start to fall, but the additional costs would start to climb. They started searching frantically for some substitutes, and you need fast forward and then you get the kerosene discovery. And what happened there was with the discovery of kerosene and a relatively low priced alternative to whale oil, you see consumers quickly making a switch. You see entrepreneurs moving into the production of kerosene and bringing it into the marketplace. And yes, the entrepreneurs benefited because they were able to realize profits in the beginning, relatively high profits.

But as competition played out, this market that Hayek so clearly described, as it started moving about, the beauty of it was is that the consumers benefited, like the entrepreneurs and the producers of kerosene, but they benefited so much more because we get the discovery of many other linked products along the production chain. And people lived better, they lived more securely because they were able to work longer or longer days and go different places and such. So really this is a Hayek and or an Austrian story. It's the rising wheel oil prices and some competitive entrepreneurs that flipped the script. Whales didn't get fished into extinction. And when you compare that story to the story that would likely play out today, today's knee jerk reaction is, well, let's slap together some governmental rules and some wailing policies to put wailing on pause. And that's a very different mindset. But what we've done with just a short little story, this narrative that's rooted in reality is we've given people, our students, especially the people with little or no background in economics, reason to pause and think about other alternatives then to quickly move to government responses.

Juliette Sellgren (18.48)

So man, my brain is splitting in two different directions. What I really want to ask, what I'm going to ask is on the relevance bit, something that I think is super beautiful about that story is that you can't know, as the people who were consuming whale oil, it wasn't really up to them whether or not their choice of oil or the movement would save the whales, right? So baked into this whole equation is the fact that to talk about math is the fact that whales were actually becoming extinct. And that's important for the forces of the market. And that obviously is not at the forefront, but it's kind of implicit, which I think almost upsets a lot of people. Or it makes it hard to put into application today. Because what I think about when I try to find examples to talk to my students about is they know today at time zero that they want to, for example, save the whales.

But what's awesome is that they didn't even have to worry back then about saving the whales. It just happened because to not have whales would be worse than to use an alternative and find an alternative and still have whales existing. The market naturally came to that even better alternative. But what's hard is students want to have a specific outcome. Let's take climate. They know that they want to reduce carbon, and it's hard to stand there and tell them, well, if you kind of ignore this or not ignore this. But if you don't force companies to think about it now, it will naturally more costly because the world incorporates this information into the way that markets work. And so I don't really know how to talk to students when the thing they care about looking forward is kind of imposing an outcome when the actual narrative is that regardless of the outcome that you want to impose, it naturally becomes a better outcome through the use of markets. And I think that's really hard to communicate or tackle as an issue. And I'm wondering if you have thoughts on that or if I'm even explaining this well or if there's a connection there.

Tawni Ferrarini (21.29)

No, I think there's a great connection there, and I appreciate the narrative. What I like to do is explain or to talk with the students about the reality, even if government had gotten involved and try to save the whales, how many instances do we have that that has actually succeeded? We lock into a policy that's very difficult to change, even though everything changes that is involved with the policy, and we have these huge lags that we have to deal with and we have to address, and we know over and over again with climate, the one thing that's going to happen, one constant is change. And so how do you track the change? There's so much data and the complexity of all the moving parts, it's hard for one policy to capture it all. So you have to think about, well, what is there as an alternative?

And this is where it's hard for us as professors, especially those that have done the reading, and then we move into the classroom and our responsibility is we've got these first year students, they may be a one course only, an economics student. How do we excite them about these ideas when they have been born and raised in an environment where they have been taught that government is the benevolent social planner, even though the only record of success that government has in human history is that of protecting individuals rights and their freedoms in providing some other sound institution when it comes to stable money and free trade, that their success record or their policy record is miserable. So we do need government, but we need this government that is limited. It protects our rights, it provides rule of law, it provides a few public goods and services that markets can't provide.

And then other than that, it's hands off. We've got to let markets do their things. So when we go back to the whale example, the real MVPs of that story of the whaling story is entrepreneurs’ profits, competitive markets. And it was because the entrepreneurs could legally profit from their brainwaves and their pursuits. They were motivated to search for energy alternatives to the pricey whale oil, and nobody knew what that alternative was going to be. But boom, we got it. Once kerosene came along, we get cheaper, cleaner energy and no whales are involved. That's an incredible story, and I think it's one that can resonate with students, and we can even bring it into the current policy space and some of the presidential debates because on both sides of the aisle, you have politicians and legislators who want to advocate for government policy to solve these problems without recognizing the weaknesses in the frailties of the systems. Because we live in a complicated world, we have so much going on. Would you want to stick with one policy, especially when it comes to climate change, understanding that the only constant in climate change is change?

Juliette Sellgren (25.16)

I like that. The only constant in climate change is change. I feel like. Okay, this is great. But I realized as we kind of continued talking about this that we assumed that, and maybe we didn't actually think this on the whole, but in the course of this conversation, we've kind of assumed that we're going to be talking to students studying economics in some capacity about Hayek. And that Hayek is relevant basically to issues that economics touches. But is Hayek an economist and is it best to sell him is maybe the wrong word, but to introduce him as an economist to people studying economics? Or are there other ways to bring Hayek into the fold?

Tawni Ferrarini (26.11)

Oh, I like that. I hadn't thought about it that way because sometimes when you place somebody in the econ or on the econ platform, people just shut down and look the other way. So maybe there's a way to bring him into the fold and have him have a seat through us while we're teaching with the students or with the listener of this podcast who knows nothing about Hayek, but is slightly curious, especially if they're interested in understanding what's going on in the world today. And some of the debates that are transpiring on the political platforms, there is an alternative to, let's say the two policy system. And that is to just have government back off and fill its limited rules in our lives and let market forces and responsible and accountable, ethical individuals go about their business. And by serving themselves, by helping others, they're going to make the world better because it's in their best interest as well as in others' best interests. So how do we take the math out of the image of Hayek? Because Hayek being an economist automatically falls into that group, even though as you recognized, he was very, he didn't work with the equations.

Juliette Sellgren (27.43)

I was just going to say, I think the whale example and talking about ways in which actually these economic scenarios do play out using history and examples and kind of as Hayek would really bring it to light when you're in a classroom talking about economics. But there are people that we want to reach and that would be receptive to these ideas, or at least should, in my opinion, grapple with them because they’re ideas worthy of responding to, even if you don't come out agreeing, that can't engage with economics or it's just too difficult. But in a way, Hayek is so much more than an economist, and I think that's why he's so compelling. I was talking to Don again, as I mentioned, go listen to that episode listeners. I think it was great. But we were talking, and it struck me just how much importance Hayek placed on information, which is maybe obvious, but more than just information.

He came at it from kind of a Platonic way. I think the more time you spend actually reading it, the more influence you see in Hayek. And Don pointed this out, which was really helpful for me, that he was really well read, very literate, spoke a bunch of languages, and so he was exposed to all of these different disciplines. And in doing that, you can start to see the influence of thinkers in other disciplines like philosophy in his work in economics. And there's something about that that makes me think you could teach Hayek in sure, a relevant policy context or a modern information context, talking about AI, for example, that doesn't necessarily, that uses economics, but comes at it from, well, this is what Hayek thought about this relevant issue given what Plato says about X. And I don't know, I was just kind of noodling on this idea, and I think there's real potential there, but I don't really know what venue to approach that from.

Tawni Ferrarini (30.03)

Oh, I think that you've made some great statements here. And as you move along in your career, you're going to be able to take Hayek into political science, into international trade courses, into history courses, the social, what is it, settings in cultural, and I mean, there's so many different spaces because the bottom line is even if you're not dealing with actual prices, and when we think of prices, we're thinking about going into a market and purchasing something and seeing a price tag. You still can read into people's behavior about what they value they do and they don't. For example, you can look at children who are playing on a playground and you see one child who's acting up and not following the rules. What do you see the other children walk away? The child's left standing. So the information and the signaling, it can come through behaviors.

And in econ, especially when we're teaching our students in micro and macro, our survey courses and even some of the upper level courses, we all understand that when we are in a space like Amazon or Facebook marketplace, that we've got these hundreds of thousands of humans who are acting and interacting in these spaces, and they're responding to price signals, they're sending them out, they're reacting to them, and then their reactions then incentivize other individuals to respond to their actions. And this is the beauty of the marketplace, and it can't be planned. It's just spontaneous. And if we take this example, the relevant one, the one the students or the new listener to economics or the curious person about economics, you can say, okay, I can relate to that. And then let's take this relatable example and the intricacies behind it and let's bump it up a little.

Let's just scaffold a little bit and let's bring it, we'll lift it up, bring the example and plant it in a different space. And I think that that is an interesting example where we can look at, if we're talking about whaling days or climate change discussions, we have to ask ourselves, are we giving entrepreneurs a green light to innovate without crazy restrictions, policy interferences and legislative distortions? Or are we stopping them from the things that are invisible and keeping them from helping not only themselves through the profits that they earn by discovering new ways to address climate change, but then they're also keeping society back from new levels and addressing big issues that impact many people. Does that make sense?

Juliette Sellgren (33.20)

Oh, that makes a ton of sense. So here's a practical question maybe, and maybe you don't think it's a practical question. So we'll see. In my mind, it's a practical question. I'm thinking about talking to people about this. How has Hayek and these ideas, how have they come into your daily life in conversation with people who don't necessarily spend their time thinking about this or in conversations where it's not relevant necessarily or obviously relevant in a way that doesn't feel forced? There's something about the beauty of it all. The beauty of spontaneous order that I think now I'm thinking about I, Pencil. I, Pencil is great, but I, Pencil is a little scary, especially when I'm thinking about someone who is thinking about national security and China and foreign affairs. And not that it should be scary, but it doesn't inspire this kind of good feeling. Awe, I can see it as interpreted as a little scary, even though I think it's really beautiful. So how does it, I guess this is turning into two kind of similar questions. How does kind of this beauty of spontaneous order among other things play into your conversations that aren't inherently about Hayek or economics and how do you communicate that? And then also how do you make it maybe less, I don't want to say scary, but less off-putting to someone who is maybe not so globalization for national security concerns?

Tawni Ferrarini (35.11)

Yeah. Okay. Yeah, let's break that up into two parts. The scary part I'd like to tackle first, and I think the scary part, and correct me if I'm wrong, is that you're worried that you can't have trust in the system or control.

Juliette Sellgren

Well yeah, they go hand in hand.

Tawni Ferrarini (35.31)

Yeah, I think they do go hand in hand in this example. I do. I mean, I may be convinced otherwise, but I think if you have what we call that stable government, that entity that is protecting your rights and is basically watching out for the things that you've just described, the scary part should be taken away. And you have to trust and believe that the government is limiting itself to doing what the Constitution laid out as its responsibilities. And some of what's happened is this mission creep of government where in addition to protecting our rights, securing our borders and providing the few public goods that exist, along with, what did I miss out on that? Oh, providing rule of law that we have a government with people who are non-specialists, designing policies that are picking winners and losers. They're helping some, but they're harming others.

And it's exhausting. As a person who is listening to a podcast and sitting in a seat and trying to make sense of it all, you don't trust the government to do what's in your best interest. How can you, and there are faces behind the government entities out there markets, you're like, oh, this is kind of scary. I'm trusting something I can't see. This is just spontaneous. Am I going to trust that if whales are being harvested to extinction, that whale oil prices will go up and eventually we'll discover an energy alternative so that every time we flip on a switch, we can thank markets for letting us light up in our houses now so we don't have to use whale oil. I don't know. That's a hard story to sell. But I think even a harder story to sell is one that we assume that these people who are in office have the knowledge of the complexity of markets to make decisions that serve people in their best interest.

When we realize from the time we get up to the moment that we go to bed, we have to make a series of choices because even our time is scarce. We can't be all things to everyone. We can't be everywhere in the same moment. And I think just kind of catering or bringing people and having them lean into their common sense may be the opening that we're looking for and is up to people like you and me who want to have the conversation with the person who's sitting at the coffee shop, who is at the bar, who's at the Pizza Hut, wherever the person is, we want to have a conversation with that person to help them understand that they can trust other humans as long as they have that even playing field. And that I think, am I right, is at the heart of the scary part of I, Pencil. You don't believe it's an even playing field?

Juliette Sellgren (38.52)

Yeah. I think that we're living in a time, and this has been shown through experimental economics, but also just various types of economics that trust is fundamental to having a functional market system and to actually having gains from exchange with other people, whether it's a relationship or it's an actual market exchange. And so the lack of trust, the facelessness of it all, I think right now, especially where there's this narrative about you can't trust them even worse than not being able to know who's on the other side is having a politician tell you actually, who's on the other side? It's the Chinese government. Wouldn't you rather it be us? I don't think that helps.

Tawni Ferrarini (39.36)

I think you're exactly right. I think you're exactly right. I really don't think it helps. And so then what do we do? I mean, as a person who's just sitting there and now we're taking our econ hats off, and you look around, and again, we get back to that swirl of political and social and economic activity. It makes everything very, very confusing. It's distorting how we go about our normal daily activities because it's front and center wherever we go, it's front and center. And it's causing us to remove ourselves from some of the things that we would otherwise be doing because we don't like all of the certainty. We don't like the risks that are involved with success and failure, especially in these places that we really aren't familiar with. So we want to stay with those things that we're familiar with. And I think that we have as a society allowed government to intrude into our lives that it's almost ubiquitous.

How do we help people realize that there's another option that we've distanced ourselves from? And I think it brings us right back to Hayek because Hayek, he himself came out of World War II. He saw the collapse of communism or the Soviet Union, excuse me, on that. We see him coming out of that in some instances, we can imagine ourselves going into that. So maybe we borrow some of the teachings and the readings and the research from Hayek and our responsibility and our charge is that we now, we make it relatable to the TikTok generation. We learn how to or engage the people who are out there and excited about these ideas. We are the people who have the knowledge, we have access to the content. Maybe we partner up with some of these people and we just start putting things out there with the hope that we resonate with large groups of people.

Wouldn't you love to have a million followers on your podcast? How do we achieve that? And most importantly, have a million followers who believe in the same ideas because at the start and at the end of everything that we do, and I feel that you're the same way when I talk about the free market economists, is that we want to make the world better by helping ourselves through our service to others. And it's purposeful service. It's not just something that we randomly think we should do. We're communicating with other people, whether it's through markets and prices or having conversations, we're finding out what other people value, and we're accepting responsibility for finding a way to mutually benefit the people that are involved and not take from some in order to give to others, especially ourselves without expressed permission and some mutual benefit.

Juliette Sellgren (42.45)

Alright, Tawni, I wish we had more time to talk. This definitely needs a part two, but thank you so much for coming on the podcast. I've learned so much, and honestly, I'm excited to get back out there and bring Hayek into my everyday life and into my teaching even more than before. I have one last question for you, and that is, what is one thing you believed at one time in your life that you later changed your position on and why?

Tawni Ferrarini (43.14)

That's a hard question. I mean, thank you for asking it. Something that I switched my, I think for me it's the importance of faith because as a child, I was brought up in the Catholic church and as many, I walked away from it. And then through my actions and interactions with others, especially some of the greats, I'm a Doug North student, who's a Nobel laureate in economics, and my conversations with him and feeling the role that faith had in their lives, and it's not always defined by organized religion. It's when you're young, you feel that you've got the world by the tail and you think you have everything you need in order to succeed in life. And then later on, there's just something inside of you that eventually emerges that lets you know that this isn't it. That our time on earth is just so limited. It's precious, but there's this life eternal. And that's where I would go with this. You asked. I answered my friend.

Juliette Sellgren

Once again, I'd like to thank my guests for their time and insight. I'd also like to thank you for listening to the Great Antidote Podcast. It means a lot. The Great Antidote is sound engineered by Rich Goyette. If you have any questions, any guests or topic recommendations, please feel free to reach out to me at great antidote@libertyfund.org. Thank you.