Three Modes of Patriotism

October 23, 2024

According to Adam Smith, not all patriotism is bad but some kinds are. Matson names two forms that Smith disapproves of: the patriotism of national jealousy and the patriotism of radical opposition.

"The true patriot, on Smith’s view, pursues partnership in commerce with the nations when possible... [Smith's vision of patriotism] balances the impulse to reform and improve with the need to preserve and protect the flower of civilization where it grows."

According to Adam Smith, not all patriotism is bad but some kinds are. Matson names two forms that Smith disapproves of: the patriotism of national jealousy and the patriotism of radical opposition.

"The true patriot, on Smith’s view, pursues partnership in commerce with the nations when possible... [Smith's vision of patriotism] balances the impulse to reform and improve with the need to preserve and protect the flower of civilization where it grows."

Patriotism places the common good of one’s patria or homeland over individual or factional interests. The classical expression of patriotism is military service, in which one sacrifices for the security or preservation of his people.

The demarcation of the patria—the relevant boundaries of a people—is a matter of shifting political history. To be a patriot in antiquity was to devote oneself to the good of the city. Polities broadened and territories became integrated, drawing together peoples into larger wholes. The integration fostered new senses of identity. In the early modern age, the object of patriotic sentiment shifted to a new political entity: the nation-state.

In eighteenth-century Britain, with the island united, a new sense of national identity took more definitive form. Indeed, there developed a notion of Britishness and a distinctly British patriotism.

These developments engendered reflections on the moral status of patriotism generally. The discussions involved a wide range of thinkers, including Lord Bolingbroke, Henry Fielding, Samuel Johnson, Josiah Tucker, Richard Price, and Adam Smith.

Discussions revolved around the questions: What serves the British common good? Who can rightfully claim the title of patriot? Is patriotism consistent with Christianity? And even: Is patriotism a virtue?

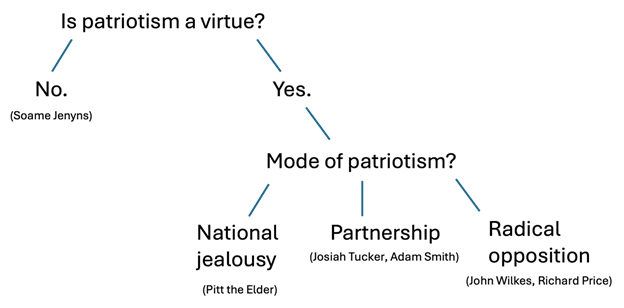

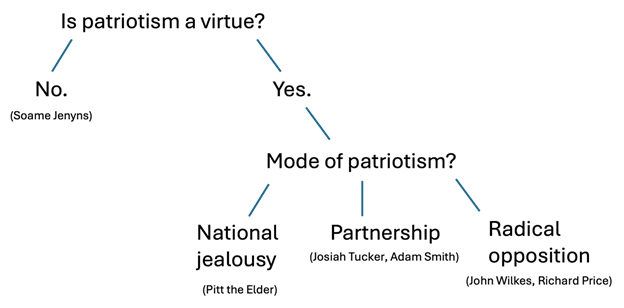

I have previously treated these discussions (here and here) and discern three distinctive modes of patriotism, depicted in the following diagram.

Here I explain the positions and representatives, arriving at a presentation of what I call the “patriotism of partnership,” associated with Josiah Tucker and especially Adam Smith.

Patriotism is not a virtue: Soame Jenyns

Patriotism is not a virtue: Soame Jenyns

Soame Jenyns was a writer, government bureaucrat, and member of the House of Commons. He became a focal figure in British discussions of patriotism. His 1776 work A View of the Internal Evidence of the Christian Religion told of the distinctiveness of Christian ethics and argued that patriotism is at odds with the Christian conception of the moral equality of persons.

Patriotism reflects the worldview of paganism in which service to the city was a means of pleasing the city’s local gods, according to Jenyns. The Christian, by contrast, owes allegiance only to the one sovereign deity who rules over all of humankind. Because of our common subjection to God, each is truly “a citizen of the world.” “His neighbors and countrymen are the inhabitants of the remotest regions, wherever their distress demand[s] his friendly assistance.” Whereas patriotic sentiment leads us “to oppress all other countries to advance the imaginary prosperity of our own,” Christianity “commands us to love all mankind” (Jenyns 1776, 50).

The tenor of Jenyns’ arguments resonates to this day, especially with progressivism and globalism. American philosopher Martha Nussbaum advances a patriotism tempered by cosmopolitanism: American students should be taught that although they “happen to be situated in the United States,” they should conceive of themselves principally as “citizens of a world of human beings” (Nussbaum 2010, 156). The political theorist George Kateb rejects patriotism altogether, contending that assertions of the virtues of patriotism involve a “grave moral error” and “a state of mental confusion” (Kateb 2000, 901). Patriotism for Kateb is morally obtuse, for it unduly prioritizes the good of a faction of humanity over humanity generally. Patriotism for Kateb is mentally obtuse because it is generally predicated on mythology—an idealized notion of country that bears very little resemblance to historical realities.

Instead of patriotism, according to these voices, we should cultivate a commitment to moral universalism. We should pursue measures that advance not just the welfare of our country, but of humankind generally; for we are all, as the Stoics maintained, citizens of the body of humanity.

The patriotism of national jealousy

Jenyns was reacting against two modes of patriotic sentiment: patriotism as national jealousy and patriotism as radical opposition.

Patriotism as national jealousy stems from the belief that the good of the nation contends with the good of other nations. If that is true, and it is also true that each person has a duty to promote the good of his or her nation, then the duties of patriotism require one to support the extension of national power through military dominance of one’s neighbors. Military dominance requires state control of resources, hence the motivation for a wide range of economic interventions, restrictions, and industrial policies.

Adam Smith described the patriotism of national jealousy, often glossed today as “mercantilism,” in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (Smith 1982; hereafter “TMS”) as a “ferocious” and “savage” patriotism. That savage patriotism—especially its attendant web of economic policies—was a prime target in the pages of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (The Wealth of Nations), a work which Smith described as a “violent attack” on the British commercial system (Smith 1987, 251).

The patriotism of national jealousy found expression in an address by the cleric John Prince delivered in 1781 before the English Anti-Gallican Society. Formed in 1745 during the War of Austrian Succession, the Society proposed to boycot French goods to boost English manufacturing while harming French economic interests and hence military power. The members forswore French claret to demonstrate their commitment. The Society exhibited “True Christian Patriotism,” said Prince.

Prince distinguished “True Christian Patriotism” from other displays of patriotic sentiment. Patriotism, Prince contended, is consistent with Christianity so long as the good of our country is pursued with “fair, just, and reasonable means” in an “enlarged spirit of Evangelical benevolence” (Prince 1781, 8–9) Beneath these remarks, however, Prince clearly perceived a tension between nations. His discourse devolved into ramblings exhibiting the kind of attitude that David Hume had called “the jealousy of trade” (Hume 1994). Prince lauded as genuinely patriotic and beneficial to the British people the Society’s opposition to “the wiles and attacks of Popery [i.e., French interests].” He praised their preference for “the honest industry of [English] countrymen,” and hence English manufacturing, over “Gallic fopperies” (Prince 1781, 24).

A man who exemplified the patriotism of national jealousy was William Pitt the Elder. Pitt’s political savvy as prime minister contributed to the ascendancy of British military power and the rise of the second British Empire. Popular for his prosecution of the Seven Years War, Pitt was lauded by the British public as a patriot for his pugnacity toward French imperial might. He also found support among merchants seeking expanded, exclusive access to colonial markets, financiers benefitting from ballooning government debt, and domestic artificers and manufacturers working in war efforts.

Josiah Tucker decried Pitt’s war efforts. In “The Case of Going to War,” first published in 1763, Tucker identified the patriotism of national jealousy as a natural product of the human impulse to jealousy, envy, and violence. The “blood-thirsty Mob,” he exclaimed, will under no circumstances “withdraw their Veneration from their grim Idol, the God of Slaughter.” The mob had been aided and abetted by seven parties seeking to advance their private gain. The first is the “Mock Patriot” and “Anti-Courtier”—clearly a reference to Pitt himself—who clamors for peace but secretly longs for wartime and the opportunity to ascend to “the ministerial Throne” (Tucker 1774, 83–84). The remaining six are: “the hungry pamphleteer”; “the Broker”; “the News-writers”; “the Jobbers and Contractors”; “the Dealers in Exports and Imports”; and “the Land and Sea Officers” (85–95).

Tucker argued in another place that it is the role of the “able Statesman” and the “judicious Patriot” to distinguish between policies said to further the common national good and policies that actually do (Tucker 1774, 44). The national interest is served by peace and the arts of commerce. These unite the interests of peoples across national boundaries. Most wars and efforts towards imperial expansion are unpatriotic in that they further private interests under the pretense of patriotism, actually harming the national interest. Though sometimes necessary, war is something to be avoided. As Tobias Smollet remarked in 1760, in the context of a criticism of Pitt, “war, at best is but a necessary evil; a cruel game of blood, in which even triumph is embittered with all the horrors that can shock humanity” (quoted in Knapp 1944, 77).

The patriotism of radical opposition

After 1688, many Whigs understood themselves as heroes who stood in the breach by resisting James II’s tyrannical aspirations. The rebellious component of Whiggery faded after 1720 when the Whigs took control of the government under the leadership of Robert Walpole. A discontented faction within the Whig party accused the Walpolean establishment of betraying the 1688 constitution. They joined with the “country” interests (opposed to “court” interests) to criticize Walpole’s extensive system of bureaucratic patronage, his buying of elections, the standing army, and the growing national debt. Walpole, in their minds, had sold the national interests in exchange for personal gain.

Such Whigs styled themselves “the Patriot Whigs.” Their mode of patriotism, which I call the patriotism of radical opposition, derived in many cases from a commitment to a set of idealized principles: notions of liberty, political legitimacy, and parliamentary sovereignty, which they believed were enshrined in the 1688 constitution. Practices that violated these principles were a usurpation or betrayal, to be opposed, even, if necessary, by the installation of a patriotic monarch who would cleanse the polity and restore liberty and sovereignty to the people. The theme of a patriotic monarch came forth in Lord Bolingbroke’s influential 1738 book The Idea of a Patriot King.

In the 1760s, the association of patriotism with ideological opposition again came to the fore in the “Wilkes and Liberty” movement. Censured, imprisoned, and exiled for inflammatory writings against the crown, John Wilkes became an avatar for popular and philosophical radicalism. His followers championed “Wilkes and Liberty” in a spirit reminiscent of the earlier Patriot Whigs. They demanded annual parliamentary elections, more extensive representation, election reform, and a cleansing of the House of Commons of corruptions. The Wilkes movement allied with the American independence movement, leveraging the American accusations of crown despotism, taxation without representation, and corruption, to call for domestic reforms in London. It was with these opposition dynamics in mind that Samuel Johnson famously quipped that patriotism is “the last refuge of the scoundrel” (quoted in Boswell 1998, 615). Patriotism as radical opposition, for Johnson, pursued ideology at the expense of practical solutions.

The patriotism of national jealousy and the patriotism of radical opposition can run together. Radical opposition to establishment power centers can be mixed with invocations that express national jealousies. Wilkes himself, for example, sympathized with Pitt’s war efforts and the arc of British military expansion. It was in fact for his criticism of the crown’s terms of peace with France that Wilkes was initially censured and condemned in 1763.

In the years leading up to 1790, a view of patriotism as a mode of radical opposition manifested in various British revolutionary associations. The most famous was the London Revolution Society, formed in 1788, the centennial of the Glorious Revolution. The members of the Society viewed themselves as the rightful inheritors of the legacy of 1688. They praised the success of the American revolution and welcomed the prospects of political upheaval in France.

One of the most famous members of the Society was Richard Price, whom Smith called “a factious citizen, a most superficial Philosopher, and by no means an able calculator” (Smith 1987, 290). In a 1789 address to the Society, later published as the Discourse on the Love of our Country, Price presented patriotism as the striving to bring about a political order supportive of the natural rights of man. Edmund Burke castigated Price as preaching a false “political gospel” (Burke 1999, 2:100). Dispensing with notions of tradition, feasibility, and political stability, Price presents the true love of country as incompatible with countenancing an unjust regime. The true patriot must transcend custom and look with clear eyes on his political order: What, he asked, is love of country in a Spaniard, a Turk, or a Russian? “Can it be considered as anything better than a passion for slavery, or a blind attachment to a spot where he enjoys no rights and is disposed as if he were a beast” (Price 1991, 179)? The patriot must dispense with customs and usages that transgress the rights of man.

The patriotism of partnership

Amidst the swirl of British ideas about patriotism, Adam Smith drafted the final edition of TMS, appearing in 1790. In the sixth part, he articulated a subtle conception of patriotism. He responds implicitly to Soame Jenyns’ claim that patriotism is not a virtue. Smith also implicitly takes issue with the other two patriotisms, even though both contain points and sentiments that find some support in Smith’s writings. Smith offers a mode of patriotism that I call the patriotism of partnership.

Against Jenyns, who denied that patriotism could be a virtue, Smith invoked ideas from his teacher Francis Hutcheson, and perhaps his fellow Glasgow alumnus Archibald Maclaine, about connections between sentiment and duty. We have a moral obligation to serve the good of humankind. But that moral obligation does not manifest in a detachment or indifference toward the local. We have the strongest obligations to care for ourselves and our families, in part because of our intimate knowledge, which gives us unique effectiveness. Our communities and countries have a claim to our attention and effort. Having been shaped by community and country, having dwelled within their boundaries, having effective connections there, we are better equipped to care for them than we are to care for humankind as it is constituted far from home.

Focused efforts to serve the good of our particular social attachments are the means by which God’s universal benevolence moves forward. The Christian ideal of universal benevolence is served not by dispensing with patriotism. In the culminating chapter of Smith’s discussion of these themes, “Of Universal Benevolence,” Smith concludes: “To man is allotted a much humbler department, but one much more suitable to the weakness of his powers, and to the narrowness of his comprehension—the care of his own happiness, of that of his family, his friends, his country” (TMS VI.ii.3.6; italics added).

A virtuous English patriotism need not conflict with a virtuous French patriotism. This understanding clearly runs against the patriotism of national jealousy. Smith writes:

France and England may each of them have some reason to dread the increase of the naval and military power of the other; but for either of them to envy the internal happiness and prosperity of the other, the cultivation of its lands, the advancement of its manufactures, the increase of its commerce, the security and number of its ports and harbours, its proficiency in all the liberal arts and sciences, is surely beneath the dignity of two such great nations. These are real improvements of the world we live in. Mankind are benefited, human nature is ennobled by them. In such improvements each nation ought, not only to endeavour itself to excel, but from the love of mankind, to promote, instead of obstructing the excellence of its neighbours. These are all proper objects of national emulation, not of national prejudice or envy. (TMS VI.ii.2.3)

The basic insight echoes The Wealth of Nations. The appreciation of mutual gains opens a vista of mutually compatible patriotisms. Decades earlier, Hume told his readers that, as a British subject, he shall “pray for the flourishing commerce of Germany, Spain, Italy, and even France itself” (Hume 1994, 351). A similar argument runs throughout the works of Tucker.

Smith was under no illusions about the prospects of international peace. He emphasized the vital importance of national defense in The Wealth of Nations as a means of preserving the social order. Civilization is fragile, and it must be defended. But supporting prudent measures to ensure national defense by no means translates to support for endless wars and imperial expansion. The means for national defense can often be acquired through the arts of commerce rather than that the arts of war.

By the late 1780s, Smith seems to have been aware that the liberal principles propounded in The Wealth of Nations might themselves become a vehicle of unproductive political opposition and a barrier to the kind of coalitional politics he preferred. In view of this possibility, and perhaps reacting to the activities of the London Revolutionary Society (maybe even specifically to Richard Price’s Discourse—the dates are tight, but it is not impossible), Smith added to TMS the discussion of “the man of system.” One possible type of “man of system” might be the patriot of radical opposition who would foist a new, idealized constitution on the people. The man of system views himself as equipped to reform the polity for the good of its members with or without their assent—his fellow citizens are like pieces on the chessboard without original principles of motion. The man of system stands in contrast to the man of public spirit who abides by “the divine maxim of Plato, never to use violence to [our] country no more than to [our] parents” (TMS VI.ii.2.16). The man of public spirit views himself in partnership with his fellow citizens.

The true patriot, on Smith’s view, pursues partnership in commerce with the nations when possible. He strives not to dismiss the functional, feasible, and possible in favor of the idealized and perfect, especially when such supposed progress would involve breaking deep social norms and conventions. Smith’s vision presupposes a largely functional political order. But it is a vision that sees that the social order is breakable. It balances the impulse to reform and improve with the need to preserve and protect the flower of civilization where it grows.

Erik W. Matson is a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center, deputy director of the Adam Smith Program at George Mason University, and a lecturer in political economy at The Catholic University of America.

This essay is part of the AdamSmithWorks series Just Sentiments curated by Daniel B. Klein and Erik Matson. New essays will be published on the fourth Wednesday of most months. You can read more about the series in this Speaking of Smith post, "Just Sentiments- Welcome!". Klein and Matson lead the Adam Smith Program in the Department of Economics at George Mason University, in association with the Mercatus Center. In the program, they study big ideas in jurisprudence, politics, ethics, and economics as they were pursued during the original arc of liberalism, especially in the 18th century in Britain.

References

This essay is part of the AdamSmithWorks series Just Sentiments curated by Daniel B. Klein and Erik Matson. New essays will be published on the fourth Wednesday of most months. You can read more about the series in this Speaking of Smith post, "Just Sentiments- Welcome!". Klein and Matson lead the Adam Smith Program in the Department of Economics at George Mason University, in association with the Mercatus Center. In the program, they study big ideas in jurisprudence, politics, ethics, and economics as they were pursued during the original arc of liberalism, especially in the 18th century in Britain.

References

Boswell, Samuel. 1998. Life of Johnson. Edited by Robert William Chapman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burke, Edmund. 1999. Selected Works of Edmund Burke. Edited by Francis Canavan. Vol. 2. 3 vols. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Hume, David. 1994. Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary. Edited by Eugene F. Miller. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Jenyns, Soame. 1776. A View of the Internal Evidence of the Christian Religion. Seventh Edition, Corrected. Dublin: W. Wilson and R. Moncrieffe.

Kateb, George. 2000. “Is Patriotism a Mistake?” Social Research 67 (4): 901–24.

Knapp, Lewis M. 1944. “Smollett and the Elder Pitt.” Modern Language Notes 59 (4): 250–57.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2010. “Patriotism and Cosmopolitanism.” In The Cosmopolitan Reader, edited by Garrett Wallace Brown and David Held, 155–62. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Price, Richard. 1991. Political Writings. Edited by D.O. Thomas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prince, John. 1781. True Christian Patriotism: A Sermon Preached Before the Several Associations of the Laudable Order of Antigallicans. London: S. Crowder.

Smith, Adam. 1982. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Edited by D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

———. 1987. The Correspondence of Adam Smith. Edited by Ernest Campbell Mossner and Ian Simpson Ross. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Tucker, Josiah. 1774. Four Tracts, On Political and Commercial Subjects. Second Edition. Glocester: R. Raikes.